Having just explored the memorial culture of a modern secular heroine, I wish to complement this with a discussion of an early medieval female saint.

Having just explored the memorial culture of a modern secular heroine, I wish to complement this with a discussion of an early medieval female saint.

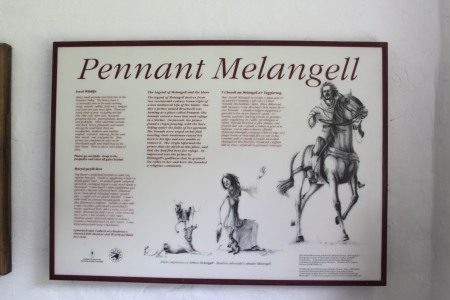

The link is that both create a distinctive pairing of person and thing. With Grace Darling it was her female form with an oar. In this case, it is a human-animal connection because I want to focus on the cult of St Melangell – possibly an eighth-century Irish princess – at her church at Pennant Melangell. In this beautiful, simple church set within a large circular churchyard in a very isolated location in mid-Wales we find a distinctive set of modern memorial culture associated with Melangell herself.

The story of Melangell is ridiculously simple and stylised. She protects a hare from hounds and the nobleman who is hunting the animal is so impressed by her deed he gives her the valley. That’s about all we know and it probably didn’t happen.

The story of Melangell is ridiculously simple and stylised. She protects a hare from hounds and the nobleman who is hunting the animal is so impressed by her deed he gives her the valley. That’s about all we know and it probably didn’t happen.

Melangell was of course a holy woman and the nobleman’s reaction was justified. Modern dog-owners rarely show the same awe and wonder when I lift my kids out of the way to stop their ill-trained beasts from gnawing at my young children. Still, I live in hope that one might one day be inspired enough to give me a valley. I guess things were different back then.

When and who Melangell really was is another story. If she is an historic figure at all, she probably was an exceptional woman in many other ways; perhaps setting up and organising a religious community with all the complex socio-political, economic as well as religious dynamics this involved. Unfortunately our sources tell us nothing of the remarkable lives of most early medieval people and Melangell is no exception here.

Today, Pennant Melangell is a focus of worship and pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint Melangell which is a remarkable structure in itself. The church and churchyard have been subject to, managed and adapted in response to, archaeological research, but it is the many images of the hare and Melangell herself that dominate the interior. Consequently, another reason why this is of archaeodeath interest is that the current building and environs are a direct result of archaeological intervention.

Hares are everywhere; in a gravestone-like slate marker at the entrance to the churchyard and within the church itself.

In addition to all her hares here, there are depictions of St Melangell herself protecting the hare and encountered by the hounds and huntsman. One is upon the heritage board itself and another is a painting within the church.

In addition to her medieval reconstructed shrine, in the newly constructed eastern apse, recreated following archaeological excavation, there is a further shrine to her. There is another on a south-facing window sill within the nave of the church.

And then, finally of course, there is her shrine itself: with fragments of original Romanesque elements and with piles of votive messages left for the saint. This is not window-dressing: the shrine is an active focus of worship and remembrance for people today and again creating a focus for the votives is a depiction of the saint with her hare.

Reading some of the messages struck home how personal and emotional the relationships are expressed; those praying that the living heal, recover, resolve their problems, those wishing to come to terms with a personal loss, those remembering loved ones and those who are speaking with the dead.

I was here a couple of weeks ago the valley and church being one of my favourites places . I had left a message at the shrine for my Little Dog who had died the weekend before and was drawn to thinking about how the site is used . One of my interests in the church is the location in a landscape covered in prehistoric burials, monuments , ancient track ways which link the valleys . Also the folklore here and over the mountains is fascinating . Corwen archaeology group are looking at the connection between sites in this mountainous area so thank you this is a very interesting article for us in the group too

It is a fabulous place indeed and I look forward to learning about the Corwen Archaeology Group’s work here.

So nice to read this older entry from 2014 in the 2020 lockdown. It brings back happy memories of Melangell’s shrine. Also happy memories of another special church on the way there, at Llanyblodwel, which has a 14th century gravestone depicting a hare in the porch –

There is also a gravestone by the church with a nice scull and crossbones. I do wonder the choices of images made and also why certain images resonate with me!