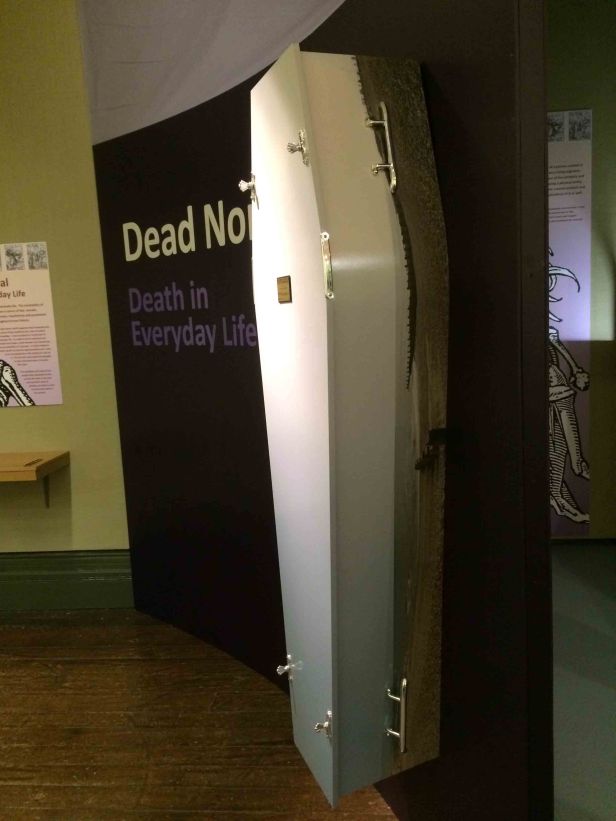

Last night, I was proud and privileged to be able to open a pairing of new exhibitions at the Grosvenor Museum Chester. Dead Normal curated by Liz Royles, and Memento Mori curated by Peter Boughton.

I’m looking forward to going back and looking in greater detail at the exhibitions in coming weeks, and taking my MA Archaeology of Death and Memory students to see them.

So here is the text of my talk and the images I deployed:

I’m delighted to be invited to open this fabulous pairing of exhibitions here at the Grosvenor Museum, a vertiable double-header of death: Dead Normal: Death in Everyday Life, and Memento Mori: Tombs and Memorials in Cheshire.

Death is something I teach and research as part of my job! I teach undergraduates about mortuary archaeology and commemorative monuments. In addition, I run the unique MA Archaeology of Death and Memory. I supervise doctoral researchers exploring topics such as early Anglo-Saxon burial practice and 19th-century Nonconformist commemoration. I also research and publish extensively on medieval and modern deathways;

Death is something I teach and research as part of my job! I teach undergraduates about mortuary archaeology and commemorative monuments. In addition, I run the unique MA Archaeology of Death and Memory. I supervise doctoral researchers exploring topics such as early Anglo-Saxon burial practice and 19th-century Nonconformist commemoration. I also research and publish extensively on medieval and modern deathways;

In addition, as illlustrated by my 2016 book with Mel Giles – Archaeologists and the Dead – I also research the ethics, politics and public engagements of mortuary archaeology with contemporary society.

In addition, as illlustrated by my 2016 book with Mel Giles – Archaeologists and the Dead – I also research the ethics, politics and public engagements of mortuary archaeology with contemporary society.

Likewise, this recent collection – Death in the Contemporary World – Perspectives from Public Archaeology – shows how archaeologists are increasingly exploring the discipline’s contributions to contemporary beliefs and practices about death and memory.

Likewise, this recent collection – Death in the Contemporary World – Perspectives from Public Archaeology – shows how archaeologists are increasingly exploring the discipline’s contributions to contemporary beliefs and practices about death and memory.

So it’s a real treat for me to be here tonight to see this brand-new exhibitions, since they directly link to my expertise and interest. I want to briefly give you some context as to why these exhibitions are, for me, so important, and also timely.

Since before the dawn of modern archaeology and science during the mid-/late 19th century, antiquaries have been digging up funerary remains to explore both the human past, but also reflect on our own mortality. Indeed, in England, discoveries of old burial urns inspired one of the greatest works of 17th-century English literature. I refer to Sir Thomas Browne’s 1658 Hydriotaphia, Urne-Buriall, or A Discourse on the Sepulcrhall Urnes lately found in Norfolk. In it, Browne reflects on what we now know to be early Anglo-Saxon cremation urns, found near Walsingham. He uses them to explore funerary practices known from the ancient world, and sees them as part of the futility of people to preserve their memories in this world:

Since before the dawn of modern archaeology and science during the mid-/late 19th century, antiquaries have been digging up funerary remains to explore both the human past, but also reflect on our own mortality. Indeed, in England, discoveries of old burial urns inspired one of the greatest works of 17th-century English literature. I refer to Sir Thomas Browne’s 1658 Hydriotaphia, Urne-Buriall, or A Discourse on the Sepulcrhall Urnes lately found in Norfolk. In it, Browne reflects on what we now know to be early Anglo-Saxon cremation urns, found near Walsingham. He uses them to explore funerary practices known from the ancient world, and sees them as part of the futility of people to preserve their memories in this world:

“Pyramids, arches, obelisks, were but the irregularities of vainglory…”

Having described many ancient writers’ views on the disposal of the dead, he concludes his essay:

“But all this is nothing in the Metaphysicks of true belief. … ‘Tis all one to lye in St Innocents Church-yard, as in the Sands of Aegypt: Ready to be any thing, in the extasie of being ever, and as content with six foot as the Moles of Adrianus.”

He concludes by quoting Lucan: “It matters not whether corpses are burnt on the pyre or decompose with time”

While Browne was inspired by the urns to write about mortality and immortality, time and memory, most people today believe, and most archaeologists can show through our research that across many different cultures past people also regarded, that Browne (and Lucan) is wrong. How one dies, and how one is mourned, disposed of and remembered, matters significantly to people past and present.

To show how archaeologists have continued to muse over the power of their subjects to reflect on mortality, let’s take another example of an archaeologist interested in mortality. 3 centuries later, writing in 1965, famous Danish archaeologist P.V. Glob concludes his book The Bog People with a further reflection on eternity inspired by the well-preserved fleshed bodies of Iron Age victims of sacrificial killing:

To show how archaeologists have continued to muse over the power of their subjects to reflect on mortality, let’s take another example of an archaeologist interested in mortality. 3 centuries later, writing in 1965, famous Danish archaeologist P.V. Glob concludes his book The Bog People with a further reflection on eternity inspired by the well-preserved fleshed bodies of Iron Age victims of sacrificial killing:

“… through their sacrificial deaths, they were themselves consecrated for all time to Nerthus, goddess of fertility – to Mother Earth, who in return so often gave their faces her blessing, and preserved them through the millennia.”

Taking forward Browne and Glob, we can regard dead bodies, tombs, and funerary monuments as mechanisms by which we come face-to-face with the dead, and thus with death. Archaeologists are thus not only historians for most of the human past where no written records survived. Archaeologists are not only historians for the vast majority of lives and deaths untouched by written records in historical times. We are also death-dealers;

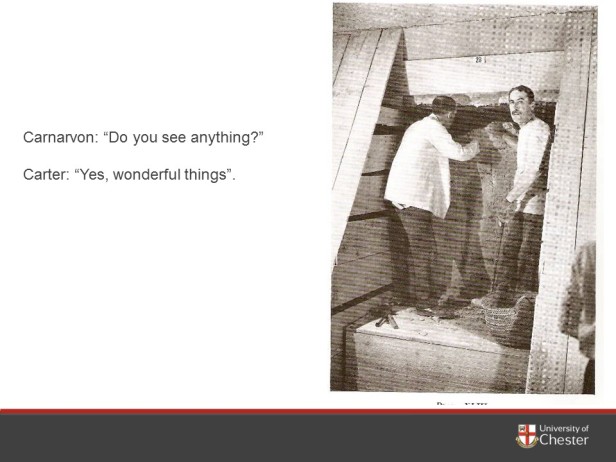

The varied, fragmented, uncanny yet fascinating, traces of past death have long allowed archaeologists to explore past societies and receive popular appeal in doing so. Here’s a more famous Howard (Howard Carter and the tomb of Tutankhamun) doing just that!

Yet, in taking on this sensitive death-dealing role – digging up, collecting, displaying and curating of the dead, and disseminating findings to the public – archaeologists have increasingly been the focus of contention and scrutiny, particularly in post-colonial contexts. Both at home and aboard, mortuary archaeology has implicated in colonial projects.

Yet, in taking on this sensitive death-dealing role – digging up, collecting, displaying and curating of the dead, and disseminating findings to the public – archaeologists have increasingly been the focus of contention and scrutiny, particularly in post-colonial contexts. Both at home and aboard, mortuary archaeology has implicated in colonial projects.

Particularly in the last 4-5 decades have seen significant shifts, driven by indigenous communities, against the public curation and display of human remains. Repatriation and reburial of mortuary remains have taken place under legal frameworks and guidelines in many parts of the globe, notably Australasia and North America.

Particularly in the last 4-5 decades have seen significant shifts, driven by indigenous communities, against the public curation and display of human remains. Repatriation and reburial of mortuary remains have taken place under legal frameworks and guidelines in many parts of the globe, notably Australasia and North America.

Even in the UK, displaying the dead has received vocal objections from some quarters, even if surveys show again and again that most people want to see, or do not object to seeing, human remains as elements of archaeological galleries.

Some UK museums have revised and removed their mortuary archaeological displays. Moreover, the reburial of human remains is an increasingly common practice following archaeological excavations in the UK;

Hence, we are at an important time for debating whether we should display the dead in museums and other heritage sites. Also, it’s a time with an unprecedented global antiquities trade in both human remains and mortuary material cultures: it’s never been more important to educate and engage people with mortuary practices past and present.

Therefore, despite the sensitivities and challenges, I remain a strong advocate of the importance of museums as places where human remains and other mortuary remains are researched and displayed. Here’s why?

As well as educating and engaging the public about past human lives and deaths, they can provide a relatively safe and buffered medium for reflecting on our mortality. They can inform and enrich our understandings of death today. practices;

Moreover, by displaying the dead, we help enact change, inspired by the past, regarding how we deal with death and the dead on a personal and a societal level. We create conversations through and around traces of deaths past.

This mirrors the aspirations of the growing ‘Death Positive’ movement which encourages us not to hide from death, it is important and timely that the Grosvenor Museum has tackled the topic of death across a range of time-periods through this pairing of exhibitions. Showing how art, artefacts, monuments and other material cultures mediate death, you will get to explore what death is, the complexity of dying, burial practice, afterlife beliefs, mourning practices and commemorative strategies.

I’m excited by the rich range of materials in the exhibitions in terms of time and space, drawing as they do on the museum’s collections and loans relating to prehistory, ancient Egypt and Rome, right through to the Middle Ages and the modern era.

The combination of art, and material culture, as well as human remains, is key to the combined success of these exhibitions. I think the exhibitions really do work in tandem.

Also important is to note how the exhibitions augment and extend mortuary themes already present in the museum’s permanent galleries – including the Newstead Gallery, and the Roman stones exhibition.

Together, they show the importance of museums for engaging us with our own mortality, to explaining to audiences young and old, the complex and varied engagements with death through time and space.

To return to Sir Thomas Browne, let me quote how he perceived ancient burial urns:

“Time which antiquates Antiquities, and hate an art of making dust of all things, hath yet spared these minor Monuments”

So let’s go forth and explore these ‘minor Monuments’ on display here at the Grosvenor Museum. We can use them to learn about death in the human past, and start new conversations about death today and tomorrow.

Dead good. I had a plant called Nerthus ònce. Alas it died

Great thoughts regarding public interface with death in the museum context. And timely coincidence with http://www.getty.edu/visit/cal/events/ev_2273.html. Underworld: Imagining the Afterlife, built around a Greek funerary vessel opening tomorrow at the Getty Villa in Malibu, CA.